Louis Sullivan

Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) was a pioneering American architect often referred to as the “father of skyscrapers” and the “father of modernism.” He played a crucial role in shaping American architecture

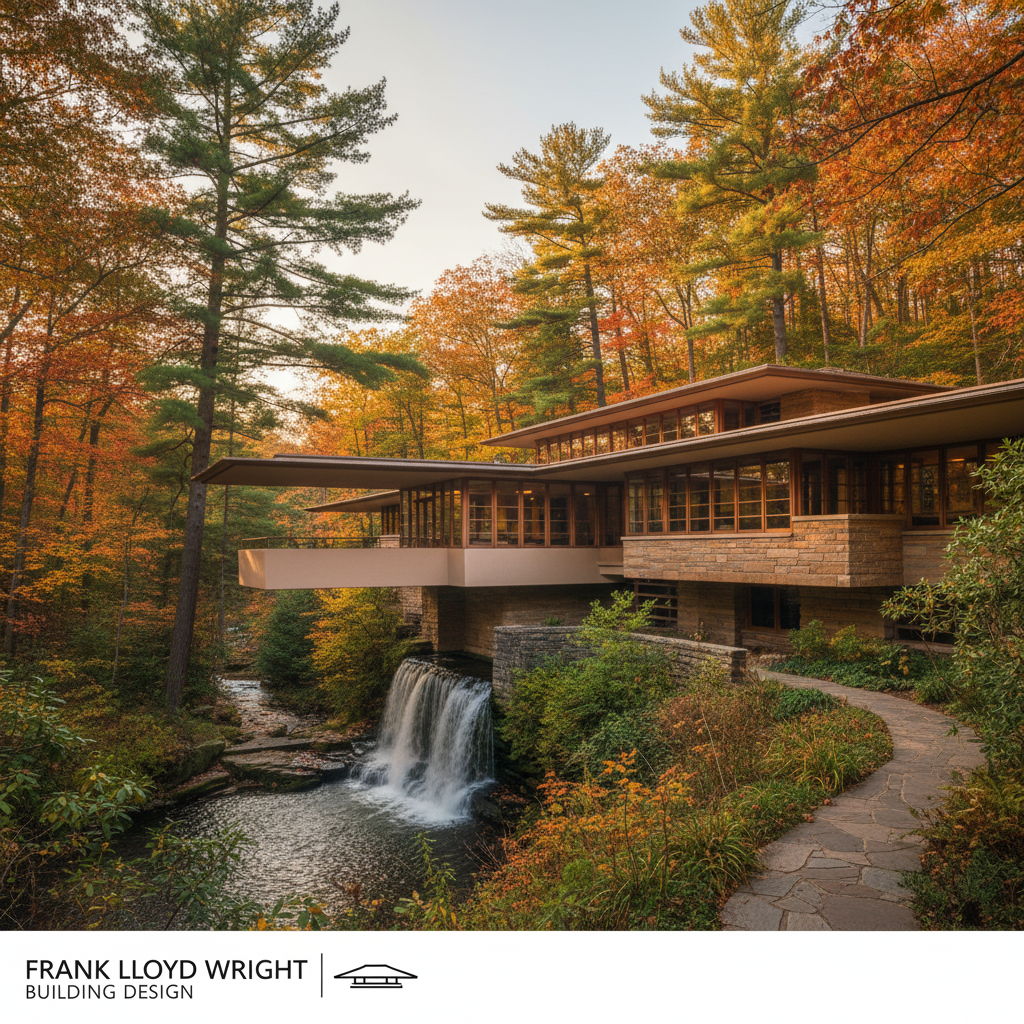

Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) was a pioneering American architect often referred to as the “father of skyscrapers” and the “father of modernism.” He played a crucial role in shaping American architecture at the turn of the 20th century and laid the intellectual and aesthetic groundwork for the modern architectural movement. His influence extended not just through his own groundbreaking buildings, but also through his mentorship of future giants like Frank Lloyd Wright.

Born in Boston, Sullivan studied briefly at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then in Paris at the École des Beaux-Arts before settling in Chicago. There, he became part of the architectural revolution that followed the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, when the city became a laboratory for new building techniques and modern urban design. Sullivan eventually joined the firm of Dankmar Adler, and together they produced a series of innovative buildings that combined structural boldness with artistic flair.

Sullivan’s most important contribution to architecture was his insistence that form should follow function—a phrase he famously coined in an 1896 essay titled “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered.” This concept became a cornerstone of modernist design. For Sullivan, a building’s shape and ornamentation should arise naturally from its intended use, rather than being imposed from historic styles or arbitrary decoration.

This philosophy was exemplified in buildings like the Wainwright Building (1891) in St. Louis and the Guaranty Building (1896) in Buffalo. These early skyscrapers featured a tripartite structure inspired by classical columns—base, shaft, and capital—but reimagined in steel and terra cotta. What made them revolutionary was not just their height or technology, but how Sullivan used ornament to enhance rather than distract from the building’s form. His intricate, nature-inspired designs were integrated into the structure itself, especially around entrances, cornices, and windows.

Sullivan’s work stood in contrast to the prevailing architectural trends of the late 19th century, which favored historic European styles. While many of his peers were dressing steel-frame buildings in Renaissance or Gothic garb, Sullivan was striving to create a uniquely American architecture—modern, honest, and reflective of the country’s spirit.

Unfortunately, Sullivan’s career declined in the early 20th century as tastes shifted toward Beaux-Arts and classical styles, and commissions dwindled. He spent the later years of his life in relative obscurity, working on small projects like Midwest banks and writing a series of philosophical essays. However, his ideas endured through the work of his protégé, Frank Lloyd Wright, and through the broader development of modern architecture.

Louis Sullivan died in 1924, but his legacy is profound. He was a visionary who saw architecture not just as construction, but as art, philosophy, and a reflection of society’s values. His insistence on structural honesty, functional clarity, and organic ornamentation paved the way for 20th-century modernism and helped establish architecture as a uniquely expressive and cultural discipline in the United States.