Louis Kahn

Louis Kahn was one of the most profound and poetic architects of the 20th century. Born in 1901 in Estonia and immigrating to the United States as a child, Kahn spent most of his life in Philadelphia, where he became a key figure in modern architecture. His work is characterized by monumental forms, careful attention to light, and a deep philosophical inquiry into the nature of architecture itself.

Kahn’s early career was relatively modest, but his architectural philosophy began to crystallize in the 1940s and 50s. While he was familiar with modernist ideas from figures like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, Kahn sought to move beyond the functionalist and machine-driven ethos of mainstream modernism. Instead, he drew inspiration from ancient architecture—Greek temples, Roman ruins, medieval fortresses—and infused his buildings with a timeless, almost spiritual presence. He once said, “I ask the brick what it wants to be, and the brick says, ‘I like an arch.’” This statement reflects Kahn’s belief that materials and form should have inherent dignity and expressiveness.

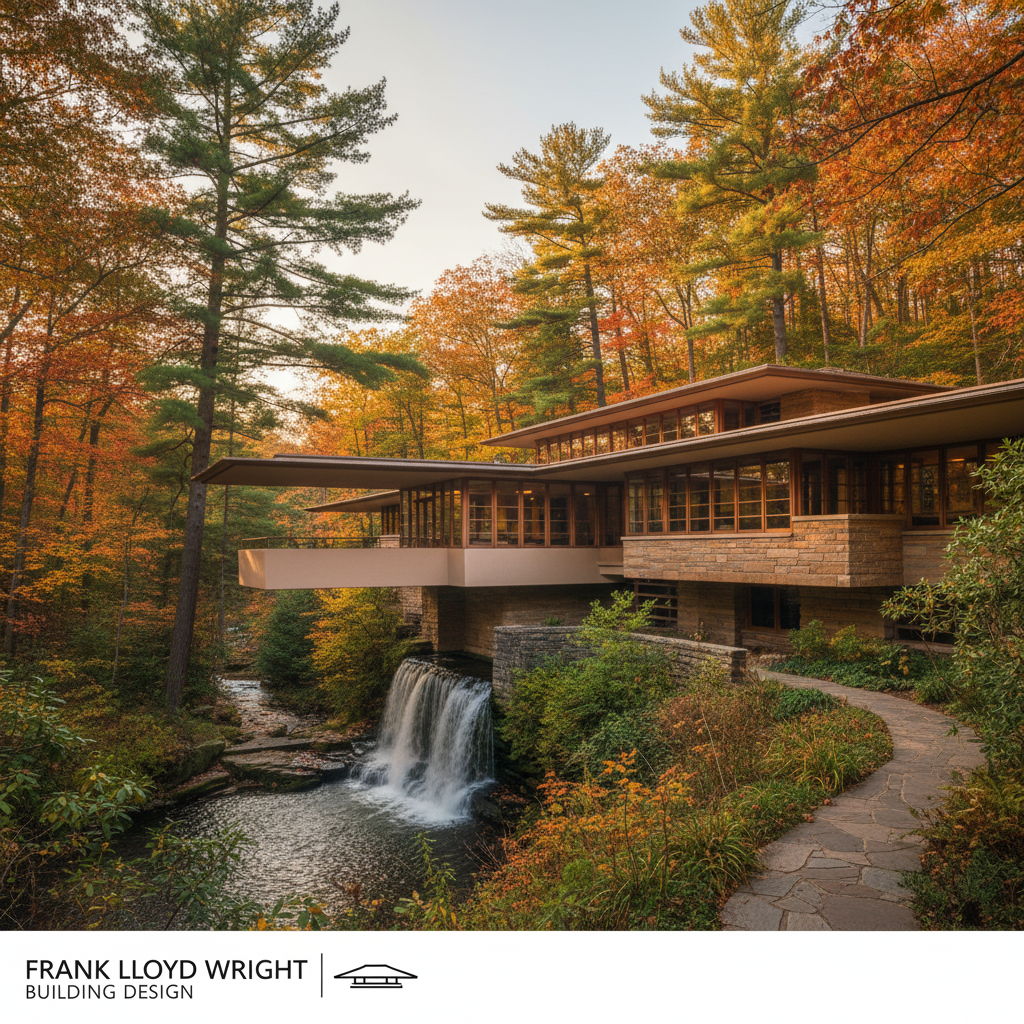

Kahn’s architecture is known for its massive geometric volumes, exposed materials, and masterful use of natural light. His buildings often feel ancient and modern at the same time—solid and contemplative, yet strikingly innovative. One of his most important early works was the Yale University Art Gallery (1953), which introduced many of the themes he would explore throughout his career: clear structural expression, rhythmic repetition, and the use of light as a shaping force.

In 1962, Kahn completed the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, widely considered one of the masterpieces of 20th-century architecture. Set atop a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, the Salk Institute features two symmetrical laboratory wings flanking a central plaza with a narrow water channel running through it. The building’s austere concrete surfaces, careful proportions, and stunning interplay of light and space make it a profoundly meditative place for scientific research.

Another iconic project is the Kimbell Art Museum (1972) in Fort Worth, Texas. Here, Kahn used a series of cycloid vaults to create a series of naturally lit galleries, using skylights and reflectors to diffuse sunlight beautifully into the spaces below. The Kimbell is often praised for its serene atmosphere and the way it harmonizes with its landscape.

Internationally, Kahn is perhaps best known for the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh (completed in 1982 after his death). This monumental complex uses massive geometric forms and deeply recessed openings to manage intense light and heat, while symbolizing democracy and cultural identity. The building is a powerful example of how architecture can express meaning through form, material, and space.

Kahn died suddenly in 1974, leaving behind a relatively small but intensely influential body of work. His ideas about architecture as a spiritual and moral endeavor have inspired generations of architects. Rather than chase trends, Kahn looked for essence—what a building wants to be, how space should feel, and how light should move through a room. His architecture remains timeless, speaking not only to the mind but also to the soul.