Singapore food security data: how a land-scarce nation stays resilient without producing much

1) The core constraint, stated in the numbers

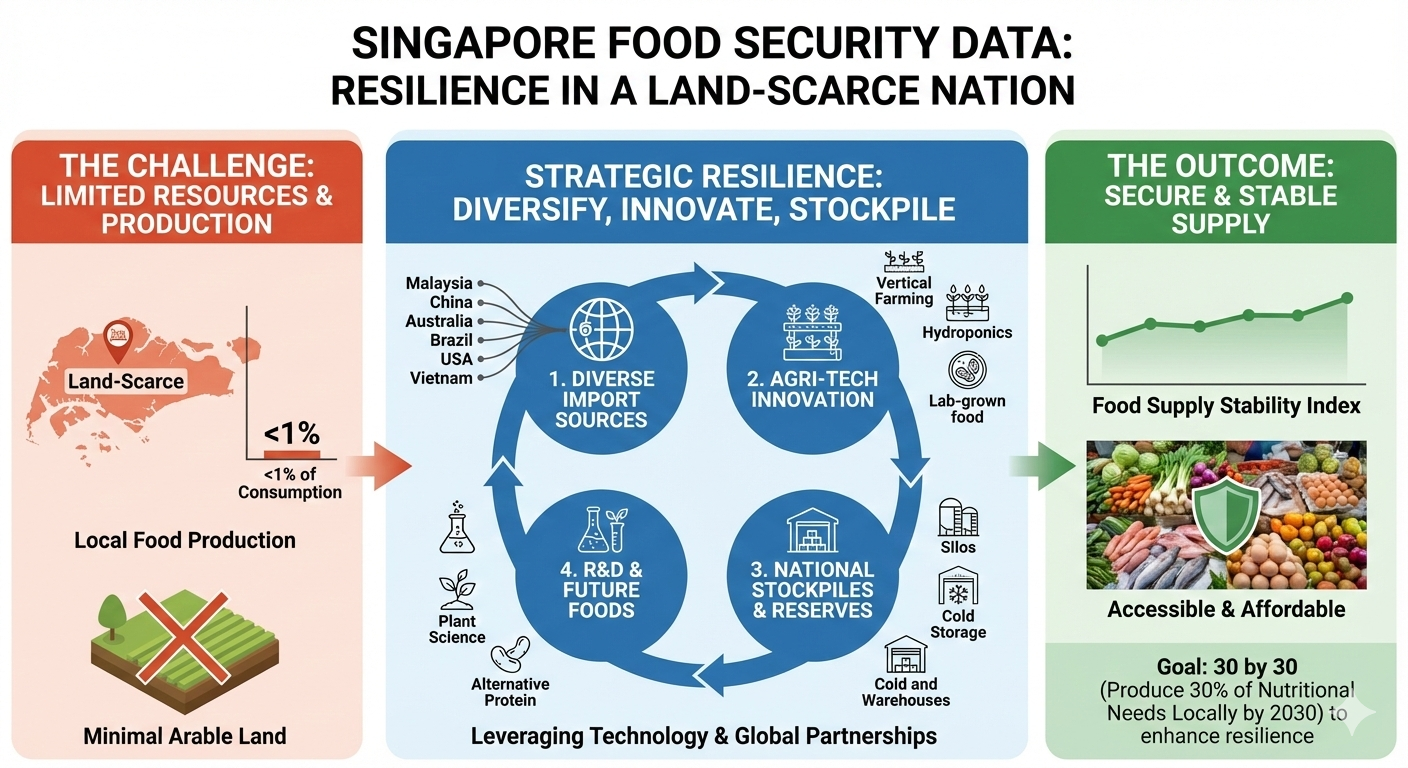

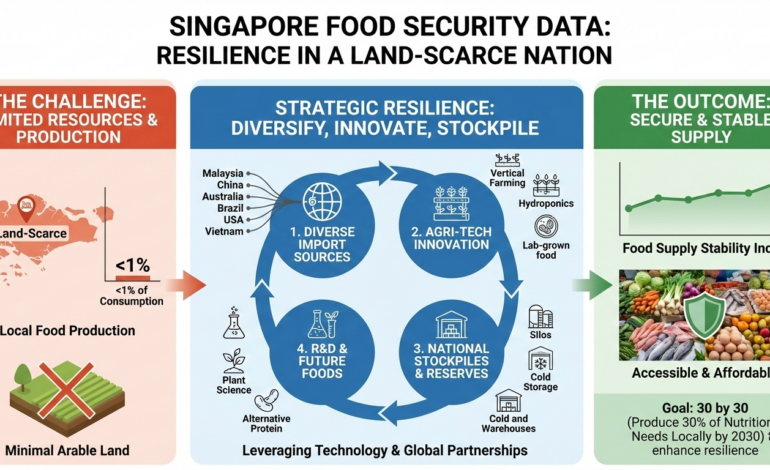

Singapore’s food security strategy begins with an uncomfortable baseline: more than 90% of the national food supply is imported, and only a small share of land is available for agriculture. Default+1 This import dependence is not a policy failure—it is a structural reality of a dense city-state whose comparative advantage lies in trade, logistics, and governance. The food system therefore has to be designed like critical infrastructure: diversified, regulated, buffered, and continuously stress-tested.

From a risk-analysis standpoint, the key exposure is not “low domestic output” but import concentration and supply-chain fragility (disease outbreaks, climate shocks, export controls, shipping disruptions, and price spikes). Singapore’s approach is best read as a portfolio strategy that reduces single-point failures across sources, pathways, and products.

2) Import diversification is the first line of defense

The cleanest indicator of Singapore’s resilience posture is supplier breadth. In 2024, Singapore sourced food from 187 countries/regions, up from about 140 two decades earlier. Default This is not just “many flags on a map.” It lowers correlation risk: when weather, geopolitics, or animal disease hits one geography, substitution is more feasible if alternative sources are already qualified and commercially active.

Diversification is paired with active source accreditation for higher-risk items (e.g., meat, eggs), where biosecurity and disease risk can abruptly halt trade. In 2024, SFA approved new sources including Portugal (pork), Brunei and Poland (beef), and Türkiye (poultry), expanding the feasible substitution set. Default+1 In supply-security terms, accreditation is “option value”: it creates pre-cleared pathways that can be activated quickly when incumbents fail.

3) Food safety regulation is a security instrument, not just public health

A common misconception is that food safety and food security are separate domains. Singapore explicitly treats them as interdependent: “no food security without food safety” is operationalized through a farm-to-fork, science-based system with inspections, horizon scanning, and risk management aligned with international standards. Default In a global shock, the temptation is to accept any available supply; Singapore’s system aims to prevent “security through unsafe imports,” which can trigger secondary crises (illness outbreaks, recalls, loss of consumer trust) that further destabilize availability.

Regulatory competence also supports diversification: if importers trust the clarity and predictability of the rules, they can onboard new suppliers faster; if exporting countries trust the accreditation regime, they are more willing to invest in compliance for market access. This governance “plumbing” is one reason Singapore can spread risk across so many origins.

4) Local production is small by volume—but strategically targeted

Singapore does not try to outgrow its land constraint; it tries to buy insurance through selective domestic capability. The latest official data show how targeted this is. In 2024, local farms contributed around 34% of hen shell eggs consumption, 3% of vegetables, and 6% of seafood. Default These shares are modest overall, but they matter in two ways:

- Eggs as a resilience anchor: Eggs are a high-frequency staple with limited processing complexity and a short supply chain. Achieving ~one-third local coverage provides shock absorption during import disruptions, especially if logistics are constrained. Default

- Vegetables and seafood as “capability platforms”: Even with low shares, Singapore builds operational know-how in indoor farming and aquaculture systems that can be scaled or repurposed when conditions change. Default

The data also point to what Singapore optimizes for: productivity per unit land, not total acreage.

5) Productivity gains show the “grow more with less” logic

In 2024, local egg production rose 13%, and egg-farm productivity increased from 14.8 million to 16.7 million pieces per hectare per year (2023 → 2024). Vegetable production fell ~3%, yet vegetable productivity increased from 227.2 to 231.4 tonnes per hectare per year over the same period. Default These are classic signatures of a high-cost environment responding with technology, process engineering, and farm upgrades rather than land expansion.

From a systems perspective, this matters because resilience is not only about shares; it is also about ramp potential. Higher productivity and more standardized controlled-environment systems can shorten the time needed to expand output if future incentives or emergency measures justify it.

6) “30 by 30” evolved—yet the underlying security framework remained intact

Singapore’s 2019 ambition to produce 30% of nutritional needs locally by 2030 (“30 by 30”) became a globally cited urban-food benchmark. Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy+1 But by late 2025, Singapore publicly reassessed and moved away from the original 2030 framing, citing land constraints and high labor/energy costs, and shifting toward more targeted local-production outcomes alongside other resilience levers. Reuters+1

This pivot is analytically consistent with the 2024 production mix: eggs are meaningfully local, while vegetables and seafood remain limited. Default The lesson for food-security scholarship is that targets must be compatible with factor endowments. Singapore’s model is not autarky; it is risk-managed interdependence, where trade remains central but is engineered to be less fragile.

7) Stockpiles and continuity planning strengthen shock tolerance

Food security is ultimately about performance under stress. Singapore’s public narrative of food resilience consistently includes stockpiling and business continuity planning as explicit pillars alongside import diversification and local production. SG101+1 Stockpiles do not eliminate dependence; they buy time—time to switch suppliers, reroute logistics, renegotiate contracts, and stabilize domestic prices.

Continuity planning is equally strategic: when importers and retailers have rehearsed alternative sourcing and distribution, the system can respond with less panic buying and fewer cascading failures. Singapore’s emphasis on industry continuity plans fits the broader governance style: codify expectations, simulate disruption, and institutionalize learning cycles. Default+1

8) Global partnerships and trade credibility are “virtual farmland”

For a land-scarce importer, geopolitical reliability and commercial trust substitute for domestic acreage. Singapore leverages strong connectivity and trading relationships to maintain access to supply across many origins. Default+1 This is sometimes described as “virtual land” or “outsourced production,” but the more precise framing is contractual and diplomatic risk management: stable institutions, predictable regulation, and credible enforcement reduce counterparties’ perceived risk of doing business with Singapore.

Independent trade analyses echo this: Singapore’s consumer-oriented food market is competitive, with diversified market shares and no single country dominating—an outcome aligned with deliberate sourcing diversity. USDA Apps

9) Alternative proteins and R&D: optionality for the long run

Singapore has invested heavily in food innovation narratives—novel foods, alternative proteins, and agri-food R&D—because technology can relax land constraints over time. Academic treatments emphasize Singapore’s strategic use of innovation policy to build future food systems under resource scarcity. Royal Society Publishing+1 Yet official and media reporting also acknowledge hard economics: scaling some alternative protein pathways has been slower and more expensive than early optimism suggested. Reuters

For a PhD-level interpretation, the key is not whether any one technology “wins,” but that the state is building a diversified option set—regulatory frameworks for novel foods, public-private R&D channels, and commercialization pathways—so future supply shocks or price shifts can be met with more than one tool.

10) A synthesized model of “food security without farming”

Putting the data together, Singapore’s approach can be summarized as five mutually reinforcing mechanisms:

- Breadth of import sources to reduce concentration risk (187 sources in 2024). Default

- Accreditation and safety governance to keep diversified trade viable under biosecurity constraints. Default+1

- Strategic domestic staples (notably eggs at ~34% in 2024) to cushion key categories. Default

- Productivity-first local farming to maximize output per hectare and maintain ramp capability. Default

- Buffers and partnerships—stockpiles, continuity planning, and reliable trade relationships—to sustain performance under disruption. SG101+2Ministry of Sustainability+2

This is why Singapore can achieve strong food security outcomes despite limited production: it treats food as a strategic system engineered for resilience, not a sector measured only by self-sufficiency.

11) Implications for researchers and policymakers

Singapore’s case challenges a simplistic equation of “food security = domestic production.” The evidence supports a more nuanced proposition: for highly trade-integrated city-states, food security is an institutional and infrastructural achievement—a function of diversification, governance capacity, market design, and adaptive buffers. Default+2SG101+2